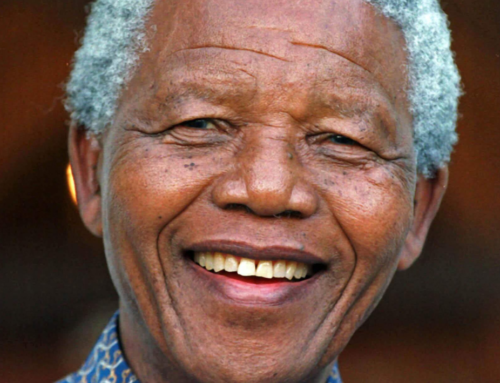

Bantu Holomisa with Judge Albie Sachs

• Dr Marianne Camerer, chair of this panel discussion

• My co-panellist, Judge Albie Sachs

• Colleagues and Emerging African Leaders

1. Learning integrity throughout my life

I started my journey with integrity when I first learnt of trust, and accepting personal responsibility, as a herd-boy. Without these values, the cattle were not properly tended to and brought home safe in the evenings.

In the early Seventies, I attended the Jongilizwe College for the Sons of Chiefs and Headmen. Here, teachers like Dumisa Ntsebeza (who in 1995 emerged as a Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC)), taught us to be informed citizens. And, in the Mqanduli congregation of the late Anglican Reverend Bacon, I was taught duty and the social value of disciplined personal conduct.

I was lucky to have had sound people in my life who taught me the value of integrity in personal life. The basics was therefore in place and applying these principles in my public life was a natural extension.

I would be remis if I don’t give thanks for Madiba’s role in my life. He made such great sacrifices for his convictions. His endeavoured to live a life of integrity. I am not saying that he was infallible – he was but a man after all – but I learnt from his courage and perseverance.

2. Living integrity: the Transkei years

My career in the military is a matter of public record. But please understand that it was the principles of integrity and having the courage of one’s convictions, that guided me in the decisions we took in 1987, which led to the Transkei being ran by Military Council. It was these values that steered us to unban 33 liberation organisations in the late Eighties and the release of all political prisoners.

We did our best to “do the right thing”. But also, understand that those years were not easy and to stick to one’s proverbial guns meant that my life had been under threat many times. During these turbulent times, I remained conscious of the principles and standards of personal conduct instilled me by my childhood protagonists.

3. Political life in the New South Africa

In 1994 I was elected to the ANC National Executive Committee and was the Deputy Minister of Environment and Tourism under Madiba’s leadership. But, after testifying at the TRC, I was expelled in September 1996. Once again, my principles landed me in hot water.

I was in essence expelled after the ANC’s national disciplinary committee found me guilty of bringing the party into disrepute, because I had made reference to an historical event of corruption in the Transkei government era whilst I was justifying to the TRC why the families of deceased soldiers, who had been killed in a 1990 Pretoria-sponsored abortive coup, had to be compensated.

In late 1996, I started on the road to the formation of the United Democratic Movement (UDM) when we consulted South Africans on the need for a new political party. Our National Consultative Forum met with Roelf Meyer’s New Movement Process, and the rest is history.

Amongst the aims and objectives listed in the UDM Constitution is: “The Party shall fight corruption and restore the confidence of the people in all Government structures”. We have batted on this wicket since 1997 and, what it means is that, integrity in public life is at the core of our work.

4. South Africa today: the lack of integrity in government leaders

The drafters of our country’s Constitution had the founding father of our democracy, Tata Mandela, firmly in their minds when they finalised their work. They made the reasonable assumption that all future presidents would always put South Africa first; respect the rule of law and uphold the Constitution. Thus, keeping the integrity of public office in good standing.

Recent events (some-of-which were confirmed by the Constitutional Court regarding the need to preserve and protect the integrity of the public office and in particular by the Head of State) have proven the contrary.

In the context of Chapter 5 of the Constitution, and other relevant legislation, there is a remarkable concentration of the President’s power of appointment – in particular that the President does so with his exclusive discretion. This observation is important. We know that both the Public Protector, and our courts, had to be invited to adjudicate in the rationality of several of the President’s appointments.

Ministers have been found wanting when it comes to the keeping their offices in good esteem. The Minister of Social Development, who presides over a sensitive portfolio, does so without integrity. She is a self-confessed fraudster who misused flight tickets to a value more than R200 000.

Maybe the system we use to appoint public office bearers, like ministers, needs review? Firstly, our electoral regime must give power to citizens to directly elect their head of state and public representatives.

Secondly, we may need to introduce a system akin to other countries, where ministers are subjected to scrutiny by a multi-party forum before they are appointed.

Generally, it seems as if the moral fibre of our society is in dire straits. The cancer of deceit and scandal has permeated to all sectors of society. In schools, we see male teachers harassing girls instead of imparting knowledge and teaching them responsibility. In religious communities, we see strange things where people are sprayed with Doom and fed snakes instead of being taught the values of trustworthiness, integrity and honesty.

Politicians and public officials are misusing public money and they are awarded public money to defend their wrongs, even when the issues at hand are personal rather than departmental.

5. Accepting the role we play as leaders: living by example

If you know something to be wrong and you accept personal responsibility for your conduct, what remains of your integrity if you go ahead and do that wrong thing? On the other hand, what remains when you know the right thing to do and you don’t do it?

When confronted by such clear and gross wrongs as I was in Transkei and later in the ANC, I was incapable of acting contrary to my very deep convictions – and never will be. Of course you have to survive in life and especially in political life. You need to be flexible where flexibility is required, when it is possible. But the ultimate test for survival in human terms is whether you can live with your conscience.

So far, I have managed to survive. I hope, when looking at my life as an example, you will feel inspired and have the courage to try to do what is good and what is right.

I thank you

Delivered at the Building Bridges Leading in Public Life – Emerging African Leaders Programme 2017

UCT Graduate School of Development Policy and Practice

5th – 17th March, Cape Milner Hotel Cape Town